Visualizing the Open Skies Treaty

Current Situation: The Treaty in Danger

Current Situation: The Treaty in Danger

The Open Skies Treaty is in danger. Signed in March 1992 and in force since January 2002, it permits 34 states in Europe and North America to conduct joint, unarmed observation flights over each other’s territory and to take images using sensors with a pre-defined resolution. The treaty also permits all state parties to request images from overflights conducted by others. Its unique feature, however, consists in the fact that during overflights, representatives of both the observing state and the observed state can sit together in one aircraft. In consequence, military officers from different states engage directly with each other on a regular basis, which increases mutual trust.

In October 2019, several sources reported that the Trump Administration is considering to exit the treaty. Since then European allies and treaty supporters in the U.S. Congress have called upon the government to refrain from taking this step. They argue that the treaty strengthens military transparency, enables confidence-building, and provides important intelligence. News from early April 2020 seem to confirm that a U.S. statement of intent to withdraw from the treaty is imminent.

Here we visualize the Open Skies Treaty from four different perspectives:

If you want to know how to fix, preserve and strengthen the Open Skies Treaty, please look here.

Why is the Open Skies Treaty important for Europe?

Why is the Open Skies Treaty important for Europe?

A picture is often worth more than a thousand words. Below we visualize the total number of (successful) flights between 2002 and 2019 to illustrate the treaty's importance. Active quota flights (left) denote flights conducted by one state over the territory of another. Passive quota flights (right) are flights over that state's own territory.

Since states can share flights (on board the same aircraft), the number of active quota flights is often higher than the number of passive quota flights. The latter is equivalent to the number of actual overflights. Under the treaty, Russia and Belarus as well as the Benelux countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) form groups of State Parties with common total quotas. A third group consists of ten Western European states as members of the now dissolved Western European Union (WEU). Although the group continues to formally exist under the treaty, its quotas are distributed individually.

Countries not participating in active flights in selected year:

Countries not overflown in selected year:

The visualization highlights two points:

1. The number of active quota flights that states conduct over the territory of others varies significantly. European states (excluding Russia-Belarus) account for more than 55% of active quota flights, whereas Russia-Belarus represents 30.4% and North America (United States and Canada) 14.2%. Likewise, the main recipient of actual overflights are European states (63.3%), followed by Russia-Belarus (30.7%) and, far behind, North America (6.1%).

2. States make different choices about which treaty members to overfly. The United States, Canada and European states within NATO conduct almost all of their flights over Russia-Belarus, plus some non-aligned states such as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, and Ukraine. Russia distributes its quota much more equally across all NATO member states. Joint Russian-Belarussian flights go primarily over Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Overall, the visualization shows that the Open Skies treaty, despite its 34 member states, consists of two camps: NATO members on the one hand, and Russia-Belarus plus some non-aligned states on the other. Moreover, European member states conduct most overflights. Thus, even if the United States left the treaty, Europe could still derive benefits from overflying Russia-Belarus. In turn, although Russia-Belarus would lose the ability to fly over the United States, it would retain the right to conduct overflights over European states and Canada, which together currently account for more than 87% of its active quota flights.

How does the Treaty's quota system work?

How does the Treaty's quota system work?

The treaty enables states to take flights together – most states do not possess aircraft usable for overflights. As indicated above, this means that one actual flight shared by several states accounts simultaneously as an active quota flight for all participants. By contrast, no matter how many states participate in one actual flight, it accounts for only one passive overflight for the observed state.

In our visualization above, we display 2060 active quota flights. This number equals 1517 actual flights (passive quota flights) that took place between 2002 and 2019. This difference stems from the fact that almost one-third of these flights are shared by two, three, or even four states. Moreover, on average, every year 9.7 % of planned overflights are cancelled for technical reasons and bad weather or do not take place because the observed party refuses to accept the requested flight path.

The Open Skies Treaty describes the procedures for overflights and their technical features down to the smallest detail. All decisions pertaining to the interpretation of the treaty are subject to consensus within the Open Skies Consultative Commission (OSCC) that convenes regularly in Vienna. Over the last 20 years, the OSCC has adopted more than 180 decisions.

Member states of the Open Skies Treaty (yellow).

Most importantly, the treaty sets a fixed passive quota for each member state. This is the maximum number of flights each state has to allow over its own territory. The number of flights a state can conduct is its active quota and cannot exceed its own passive quota. The distribution of treaty quotas roughly corresponds to the territorial size of the states.

| 42 | Russia/Belarus, United States |

| 12 | Canada, Germany, France, Italy, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom |

| 7 | Norway, Sweden |

| 6 | Benelux, Denmark, Poland, Romania |

| 5 | Finland |

| 4 | Bulgaria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Greece, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia |

| 2 | Portugal |

These treaty quotas, however, merely denote the maximum of flights that are theoretically possible. In practice, State Parties negotiate the actual distribution of active quota flights each year anew. This usually happens in October when the OSCC meets with representatives of various national verifications organizations. In addition to these annual quotas, members of the Western European Union (WEU) group (Benelux, Germany, Greece, France, Italy Portugal Spain, UK) allow the State Party Russia-Belarus to conduct a small number of flights above its maximum quota (42 flights) until the respective passive quotas of the recipient states are exhausted. For example, as our visualization shows, in 2017 Russia and Belarus used their full quota. The Western European States (former WEU policy) allowed Russia-Belarus to conduct 10 more flights, including two more flights over Germany. In total, Russia-Belarus thus conducted five flights over Germany, which, nevertheless, did not exhaust the country’s passive quota (6) possible for one single State Party (50%-rule).

NATO members, on the other hand, have agreed not to conduct flights over each other. Hence, most states, except for Russia-Belarus, Hungary, and Ukraine, do not exhaust their treaty quotas. The United States, for instance, has never conducted more than half of its treaty quota (42 flights). Germany conducts three-quarters of its permitted number of flights on average, while most other states use less than 50% of the treaty quota.

Which sensors and aircraft do State Parties use?

Which sensors and aircraft do State Parties use?

When conducting overflights, the Open Skies Treaty permits the usage of four different sensors with fixed maximum ground resolutions:

- Optical cameras, 30 cm

- Video cameras, 30 cm

- Infra-red line-scanning devices, 50 cm

- Synthetic aperture radars, 300 cm

In practice, however, only optical and video cameras are in use, since member states have not yet certified the other options on aircraft. Currently, member states are in the process of modernizing their equipment by changing from black and white wet-film to four-color digital cameras. While the maximum resolution remains the same, the costs for developing and duplicating images will decrease.

IGI DigiCAM-OS airborne camera systems installed in the new German Open Skies aircraft A319.

(© Lufthansa Technik AG / Fotograf: Jan Brandes)

IGI DigiCAM-OS airborne camera systems installed in the new German Open Skies aircraft A319.

(© Lufthansa Technik AG / Fotograf: Jan Brandes)

The planes used for overflights are without exception multi-engine transport aircraft. This is primarily for practical reasons. Overflights, especially those shared between several State Parties, sometimes need to accommodate seating for more than 20 persons.

The United States operates two aircraft of the same type (OC-135B). Russia used to operate two different types – one Tu-154M and five medium range An-30. In 2011, it unveiled a third one – the Tu-214 OS. After successful certification as required by the treaty, the aircraft started to operate in April 2019.

Canada, France, Hungary, Romania, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine each operate one aircraft type. However, Canada and France share a single sensor pod, the Special Avionics Mission Strap-on-Now (SAMSON pod), which can be mounted under the wing of Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft. Until 2013, the sensor was also shared by Benelux, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain within the so-called "pod group". The United Kingdom used to operate a modified HS Andover military transport aircraft before it was released from service in 2008. Moreover, Bulgaria operates an An-30 but has stopped to conduct flights in 2019.

All other states need to rent aircraft from those countries that operate Open Skies aircraft. More than 20 years after its first Open Skies machine (Tu-154M) was destroyed in a tragic accident over the Atlantic, Germany is currently expecting the certification of its new Open Skies aircraft – a converted Airbus 319 CJ. Flights are expected for 2021.

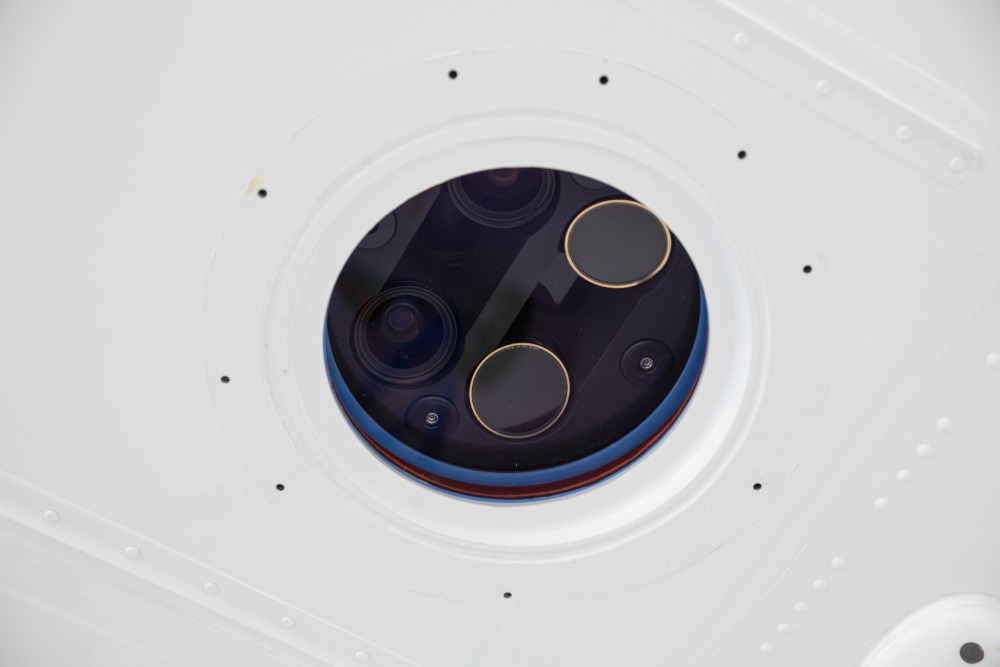

Bottom view on fuselage of new German Open Skies aircraft A319 showing installed camera systems.

(© Lufthansa Technik AG / Fotograf: Jan Brandes)

Bottom view on fuselage of new German Open Skies aircraft A319 showing installed camera systems.

(© Lufthansa Technik AG / Fotograf: Jan Brandes)

There are four basic options to use aircraft for overflights: First, states that own aircraft can conduct flights individually. Second, aircraft owners can share flights with other State Parties. Third, the taxi option: Here, the observed state provides the aircraft. Finally, states can lease aircraft from other states to conduct their overflights independently. As we show below, this is common practice. For example, Sweden has provided its OS-100 (Saab-340) aircraft to other countries 75 times since 2002. In the same period Romania has lend its aircraft (AN-30) 29 times.

The treaty also specifies airfields for the starting and ending of overflights, the points of entry to and exit from the state and even airfields for refueling. For example, Russia and the United States have four designated Open Skies airfields each, while Germany possesses two. Finally, the treaty sets the maximum distance for flights from each of these airfields.

The general timeline for conducting an overflight looks as follows:

A state wishing to conduct an overflight needs to notify the (other) state that it wants to overfly at a minimum 72 hours before its observation aircraft arrives at the point of entry. At least 24 hours before beginning the actual observation flight it must submit a mission plan that provides details about the flight path, the distance, and the estimated flight time, among others. The observed party has the right to propose changes to this mission plan. If that happens, the parties can negotiate for a maximum period of 8 hours. If negotiations are successful, the observing party can take off for the observation flight. If there is no agreement, the observing party can cancel the flight.

The observation flight has to be completed 96 hours after arrival at the point of entry. First, however, officials of the observed party inspect the aircraft, the sensors and their associated equipment onboard to ensure treaty compliance. After the flights are completed, both parties sign the mission plan, which the observing party provides to all other states within a week.

How will a possible U.S. withdrawal affect the Treaty?

How will a possible U.S. withdrawal affect the Treaty?

A possible U.S. withdrawal would endanger the future of the Open Skies Treaty. The United States would forego an important confidence-building instrument in its relations with Russia. European allies would, in addition, lose important intelligence, since most of them do not possess reconnaissance satellites. Hence, a withdrawal would not only negatively affect the United States, but also its NATO allies and ultimately all remaining member states.

As we show in our visualization above, the United States has conducted 201 successful quota flights since 2002. More than 66% of these flights were directed over Russia (134), 23% over Russia-Belarus (47), 9% over Ukraine (18), and a single flight over Georgia and Sweden each. The United States thus conducted significantly more quota flights over Russia than vice versa (77 flights since 2002).

A U.S. withdrawal from the treaty would prevent the state group Russia-Belarus from conducting flights over U.S. territory. Assuming that their interest in conducting overflights remains stable, they could redistribute previous U.S.-bound flights over Europe and Canada. Such a redistribution is possible in principle. In the past, Russia did not exhaust its allowed treaty quota for most of the European states, with the exception of Portugal, Spain, and Greece. The treaty, however, does not require countries to exhaust their allocation of flights. Russia may therefore choose to reduce its annual number of flights instead.

The following visualization shows U.S. active quota flights in more detail. In total, the United States conducted 112 flights with its own aircraft OC-135B between 2002 and 2019, between 7 and 8 flights annually in recent years. 57 of these were shared flights with other European members or Canada. During the same period, the United States conducted 89 quota flights onboard of aircraft owned by European treaty members.

A potential U.S. withdrawal would end all shared flights on U.S. aircraft, but it would also create room for non-U.S. partners on European aircraft. The remaining treaty members should therefore be able to compensate for the loss of U.S. aircraft capacity under the current provisions of the treaty.

An alternative scenario is possible: The current capacity of European aircraft could be used to address one often-cited reason for a potential U.S. withdrawal: the cost of replacing its aging OC-135B, which are more than 50 years old. European member states could extend existing aircraft lease arrangements with the United States, particularly once the new German Open Skies aircraft becomes operational. Thus, the United States could remain in the treaty but avoid new investments in aircraft, while all member states would benefit from the continuation of the successful Open Skies regime. A win-win situation.

About Us

About Us

Alexander Graef |

Alexander Graef joined the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg in March 2019 as part of the project Arms Control and Emerging Technologies. He holds a BA in Cultural Studies from the European-University Viadrina and an MA in International Relations from the Free University Berlin and the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO). His PhD thesis (2019) at the University of St. Gallen explored Russian experts and think tanks in the field of foreign and security policy. In 2017-2018 Alexander was a Doc.Mobility fellow of the Swiss National Science Foundation at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow. He is part of the FLEET-network of young experts specialising in security and cooperation in wider Europe, founded by the Regional Office of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (ROCPE) in Vienna.

Alexander Graef's research focuses on conventional arms control in Europe. He is particularly interested in Russian foreign and military policy, the sociology of international relations and the role of (defense) intellectuals, experts and think tanks in public debate and policy formation. Methodologically, he applies different approaches to social network and discourse analysis. In his current policy work, he analyses the perspectives for confidence and security building measures in the Baltic and Black Sea regions and the developments within the Russian military and defense industry.

Moritz Kütt |

Moritz Kütt joined the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg in August 2019 as part of the project Arms Control and Emerging Technologies. He studied physics and political science at TU Darmstadt. In 2016, he received his PhD in physics from TU Darmstadt, working on the role of Open Source Software for trust and transparency in nuclear arms control. Prior to his time in Hamburg, he was a frequent attendee of Princeton University's Program on Science and Global Security. First, he was a Visiting Student Research Collaborator (2015-16), funded through an ERP scholarship by the German Academic Scholarship Foundation, and later a Postdoctoral Research Associate (2017-19).

In his research, Moritz develops new approaches and innovative tools for verification of nuclear arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament agreements. These approaches and tools seek in particular to enable non-nuclear weapon states to participate effectively in such verification activities. Besides classical instruments, he studies how new technologies (e.g. Open Source Software, Virtual Reality, Robotics) can be used for existing and future verification tasks. Currently, he is working on verification options for the recently negotiated Treaty on the Prohibitions of Nuclear Weapons and possibilities for new confidence-building measures in the European arms control context.

Changes and Updates

Changes and Updates

As this website is constantly updated, previous versions are reported here.

- March 30: Initial version of the website (archived version)

- April 10: Small changes: Clarified joined flights, WEU flight rules and added short note on new German aircraft (archived version)

- April 16: Major revision (archived version):

- Modified main visualisation to show difference between active and passive quota flights more clearly

- Added new visualization on aircraft use, sharing and leasing

- Added section on effects of a potential U.S. treaty withdrawal

- April 27: Small changes to English version. New Russian version released.